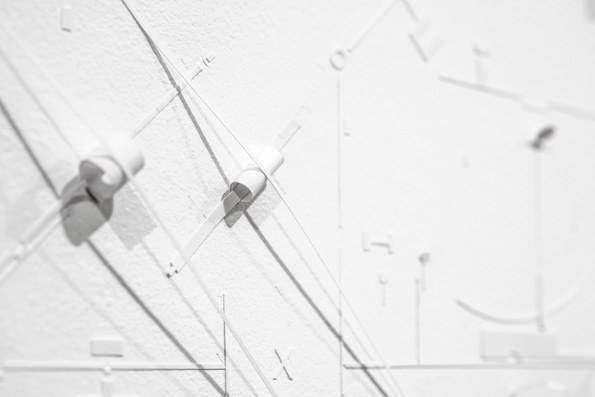

Here I am in Venice, wandering sideways to start, as is my predilection, rather than taking the main avenue in from the garden’s front entrance. I am soon at this stalwart, clean-lined building busted out, with large white-framed panes of glass in various states of shatter. At angles to each other, they are composed architecturally, like upright tectonic planes caught in stasis. This building, the Nordic pavilion—presented, this year, only by Norway with artist Camille Norment, is open, permeated, tipping out while it tips into its capacious central space marked in one half of the ceiling by microphones that remind me of the special space and anticipation of a recording studio. Although these mics only play out, they also draw in. They are receivers, (figuratively) having received before, and they are effectors that reach even further to sound the body of the building through excitors attached to resonating panes of glass. They are now playing the surround of Norment’s component sound work, a subtle multi-toned drone in glass and female voice. Light and soft but edged by the run of a wet finger along the break of a glass harmonica’s notes, I watch people stand under the mics as I do, lingering yet wavering as if naturally trying to touch the sound in the material way the building does./ In Norment’s work I have source and cause, sound as both protagonist and possible assailant, sound as both constant and transitory. We have the big bang, music to create a universe and ‘in the beginning was the Word’. In so many cultures, sound as vibration and resonance has an unequalled capacity and power. Conceptually, sound occupies quietly here while its context suggests otherwise. And more viscerally, sound and physical structure are made equal in an exploration of spatiality across media and the senses, in a space that is both inside and outside, uncompromisingly physical, yet, for me, ultimately indeterminate. As part of the Venice Biennale this stands out, this uncompromising ability and courage to work so fully with form, media, and concept in a particular space.

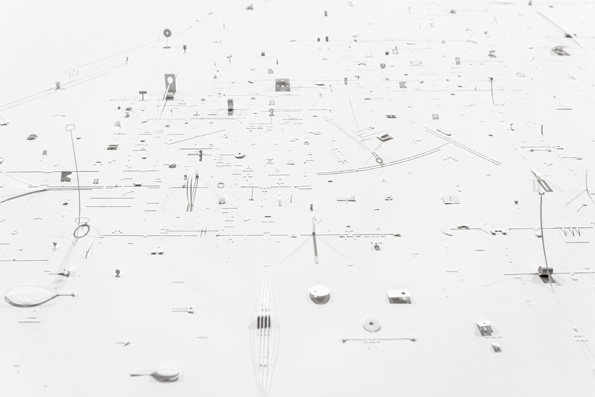

At the end of the same sideways path, is Uruguay. Tucked in behind the relatively massive structure of the Australian pavilion, you could easily miss it, and I’d say many did, unfortunately for them. I hesitate before going in, because you can’t see everything, and this is such a ‘modest’ looking pavilion... But just in the entrance I see the start of Marco Maggi’s work: a line up of sharp pencils held like arrows in bows, in a row, a quiver, point as focal point, drawing as poised and held within an armature. Inside, I take a moment to try and calibrate what seems to be a moderate and empty white-cube room. But it’s far from empty. It is occupied by the lay-out of thousands of small markings, indistinct given their nature of cut white sticker on white wall, but distinct in their extraordinary individuality. They run up and up, and along, pacing out this room with the exactitude of deliberate tiny gestures in lines and connections./ The history of language is in residence here. The potential of words and our desire to hold them, pick them up, play them out, and roll them down the river (as Neruda says), in different configurations, with the same, yet always different constituents, is core. I don’t even think of the futility of trying to photograph this, subtle intricacy. I just soak it up, with a weird kind of hum threatening in the back of my throat. I wander along and I don’t specifically wonder. I let the possibility of every run and connection, every configuration, emerge like its part in the ultimate possibility of language, the reason why I write in the first place, because there is, after all, always a process of making involved./ Three months, that’s what someone said was the time taken by Maggi to work this up, and I can imagine it, thousands of minutes over about 90 days (I guess at 54,000 minutes in that many days). Obsession and care going hand-in-hand, with the canal rising in and out a stone’s throw from the room-as-studio./ I think of what always amazes me when I write poetry: that I can change one word, insert one break, and correspondences immediately morph and change as if I’ve knocked something down in a game-line of dominos. Would Maggi have got this close as each piece went down? I’m absolutely certain of it. / Looping and leading who knows where. Part drawing, schematic, hand-cut and laid circuit board, central nervous system, epic poem.

Nordic Pavilion, 2015 Venice Biennale. Cammile Norment's sculptural installation, photos by Jodie Dalgleish.

2015 Venice Biennale, Pavilion of Uruguay, work by Marco Maggi, photos kindly provided by Marco Maggi: